"How did a writer get a story in his head onto a comics page?"

This week I read the comic scripts for Grant Morrison and Dave McKean's Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth and Neil Gailman's Calliope. I have read the finished version of Arkham before, but never Calliope. So reading the script for each was a different kind of experience.

The most helpful part of the experience was in reading Gaiman's introduction for his script. He talked about the difficulties he had with allowing one of his scripts to be published — comparing the experience to a magician sharing his secrets, or being allowed to explore the sets of a movie that was in the process of shooting.

He reveals that once upon a time Alan Moore showed him what a comic script looks like by laying it out on a piece of notebook paper for him.

Gaiman tells us there really is no set way to write a comic script. Some writers break down every little detail, draw doodles of what the paneling will be like, and some don't. Some write to the artist and some writers don't care who the artist will eventually be. Some writers follow more of a movie script style where they only write in dialogue and actions and let the artists decide how everything will look. There are also some writers who do their own art (and sometimes coloring and lettering as well).

Gaiman himself writes his comic scripts as a letter to the artist — something he says drives his editors nuts because he always has to know what artist he will be working with before he can finish a script. For this script he breaks things down by panel and includes details about how things look and feel (e.g., gloomy). He also says he makes a doodled version for every comic he does to help him know how many panels will be on each page. Gaiman says that this is only an example of how he writes for Sandman. So, even in only one authors case the script may not always look the same.

In Morrison's introduction to the script he talks more about the process of writing Arkham and the inspirations for the themes of the book. The script itself is heavy with detail. Every page gives feeling and symbolism to be used in the comic. And in this case Morrison has put comments in footnotes for most pages to give even more information on how certain scenes and looks have been changed, where things are from, and other little details. Morrison does not break things down by panels, giving McKean more free reign to decide how things will be put on the page (and he does so very effectively). Morrison is also writing to the artist and adds in little references (to stories from his own life where relevant or to specific information about the symbolism being used).

So What?

I think the habit of talking to the artist within the script is probably typical. If I were to write a comic script I don't think I'd be able to help but think of the artist as my audience to address the actions and details of my script to.

I'm reminded of McCloud's Making Comics where he starts the comic by saying, "There are no rules . . . And here they are!" The exact style of the script depends on the writer but I assume most, if not all, comic writers tend to follow a typical sort of script format (as far as set up of dialogue and action goes, font, and cases of upper and lowercase text).

And finally there was a small mention of what an editor of comics does! Gaiman says they make sure everything makes sense and is getting from place to place on time, and that everyone is getting paid. From this I gather that the editor is a sort of middle man between the various people involved in getting the comic finished and published. I may just have to try to contact a comic writer or artist to ask more about the editors they have worked with.

Quotes

(all by Morrison from his introduction to the script and the script itself)

"The Moon card then, represents trial and initiation -- the supreme testing of the soul, where we must face our deepest fears, confront them and survive or be broken. In this single image are encoded all the themes of our story."

"The story's themes were inspired by Lewis Carroll, quantum physics, Jung and Crowley, its visual style by surrealism, Eastern European creepiness, [etc.]. The intention was to create something that was more like a piece of music or an experimental film rather than a typical adventure comic book. I wanted to approach Batman from the point of view of the dreamlike, emotional and irrational hemisphere [. . .]

It took a year to research and plan and was written in one fevered month in 1987, generally late at night and after long periods of no sleep. [. . .] I found out later the script had been passed around a group of comics professionals who allegedly shit themselves laughing at my high-falutin' pop psych panel descriptions. Who's laughing now, @$$hole?"

Monday, March 01, 2010 | Labels: arkham asylum: a serious house on serious earth, comic scripts, dave mckean, grant morrison, neil gaiman, sandman | 0 Comments

"The graphic storyteller has to be willing to expose himself emotionally."

This week I read Will Eisner's Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative. Eisner was a major player in how comics look today. In McCloud's books he frequently mentions Eisner's work and points readers to his instructional books on making comics (like GSaVN). This particular book was written in 1996 and given an update in 2008 as a nod to Eisner's desire to keep his books as current as possible.

Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative

"Indeed, visual literacy has entered the panoply of skills required for communication. Comics are at the center of this phenomenon" (xv).

Eisner discusses most of the same things that McCloud does in Understanding Comics and Making Comics. One such issue has to do with stereotypes. Though McCloud discusses finding interesting ways of overturning stereotypes, Eisner mentions stereotypes as being an inescapable part of comics. Since effective communication is essential in comics I can see why stereotypical characters are inescapable. You can't devote a ton of panels and pages to every single character without detracting something from the story as a whole. I think this also connects to what McCloud had to say about archetypes and using them to your advantage.

Another thing Eisner mentioned in connection with making characters easily recognizable was to make characters resemble an animal. So, not only are human stereotypes present in comics... but so too are animal stereotypes (e.g., making someone who is untrustworthy have a snake-like look). And these stereotypes do serve a greater purpose (i.e., making them instantly recognizable — showing your reader something about a character without having to tell them right away).

"The reader absorbs mood and other abstracts through the artwork. Style of art not only connects the reader with the artist but it sets ambiance and has language value" (150).

Eisner also discusses, as McCloud does in his books, the use of text design to show the nuances of emotion. For instance, making the text larger in a dialogue box for a character who is yelling. He also discusses the use of symbols to help a reader understand what is taking place. Like when a character is carrying a knife or a gun it is the way they are holding or carrying that weapon (or the design of the weapon itself) that tells the reader upon first glance what that characters intentions are. Essentially every detail of a comic is working to create a seamless whole between art and text, which keeps a reader engaged and ensures they are not needlessly removed from the story.

"Once the reader's attention is seized it cannot be allowed to escape" (51).

Empathy also goes along with this idea (of keeping the reader engaged). The reader stays connected to the story and to the main characters through empathy for the characters. The readers get attached to characters who respond to things in a way that the reader could see themselves responding similarly to. This information immediately made me think of when people complain about how a character is acting and when it causes them to poorly review things. In a lot of these cases I think it probably is because the character is acting in a way that is contrary to how they feel they should. It makes me think of a quote I read somewhere that says something like, "The difference between fiction and reality is that fiction has to make sense."

Most interesting and different from what information I took away from McCloud's books was that of the relationship between writer and artist. Though Eisner says that ideally the writer and artist are the same person he acknowledges that it is now far more typical for there to be a different person in each role (and for there to be teams of people working on one comic).

The process the writer goes through is much different when writing a comic than it is when writing a novel. First the writer must start with their concept and think about it in terms what can be translated into images. The dialogue seems to be much less important than the descriptions the writer will use to detail what should be seen in the art. "The dialogue supports the imagery — both are in service to the story" (113).

The author essentially writes for the artist — the dialogue is for the readers but the description is for the artist. A writer might give a few paragraphs of internalization for their characters in the script but what actually makes it in to the physical appearance and art is up to the artist. The artist has to take into account the entire story and make decisions about how much or how little to show in the design and gestures/posture of the character in order to get the meaning across to the reader.

Eisner points out several things to watch out for during your process. One such thing is the fact that the process from the original idea for the comic in the mind of the writer... all the way to your finished product being in your readers hands... can lead to a lot of miscommunication between your team. It pays to be very clear on what you envision so that if you do have a specific idea about something it won't be lost in translation from person to person. Another interesting point has to do with the consideration of your reader... In film the storyteller doesn't have to take literacy or reading ability into account in the same way that a comic artist does. The storyteller must always keep their audience in mind so that they can create images that correspond with their readers imagination. He also mentions that today the attention span of most is low thanks to TV and the artist/author can't ignore this fact.

A final connection I found between Moore, Eisner, and McCloud was in their mention of writing stories that were of no real substance (or tepid, barely readable shit as Moore put it). Moore and McCloud both mention it as a negative thing, while Eisner acknowledged the existance of such stories without much judgement, other than the following pointed comment about where the artist/authors true interest is.

"The market, therefore, exercises a creative influence. The graphic storyteller, in pursuit of the market, will give sovereignty to the graphics. The graphic storyteller in the retention of readership will keep graphics in service to the story" (156).

So What?

Eisner's book was definitely a cross between Moore's book of essays and McCloud's books (which are entirely in comic form and do the reader the favor of showing and telling). I saw my first real mention of an editor in here; however, it was only a brief drawing with "editor" labelled overhead with the aim of showing us how miscommunication between different team members happens easily.

His mentioning that the author is writing to the artist made me eager to do some comic script reading (which I will be tackling next week!).

Sunday, February 21, 2010 | Labels: graphic storytelling and visual narrative, will eisner | 0 Comments

Comics is a medium of fragments --

"Comics is a medium of fragments -- a piece of text here, a cropped picture there -- but when it works, your readers will combine those fragments as they read and experience your story as a continuous whole" (129).

This week I finished up Scott McCloud's Making Comics and started on his other book Reinventing Comics.

Making Comics

Character Art

McCloud and his enjoyment of list making was ever present as I continued my reading. For your character art you must keep the following in mind :

1. character design (and character design needs an inner life, visual distinction, and expressive traits)

2. facial expressions

3. body language

The most important and least understood, according to McCloud, is the inner life of the character. It's important to understand at least the basics of your characters back story and how they came to be the person they are. Knowing this can help you to understand their motivation and how they will react to their surroundings.

"These [back stories] don't have to be too elaborate, especially for minor characters. In fact, obsessing too much over such minor details is a classic beginner's mistake. But be on the lookout for factors that color your characters' everyday outlooks, help or hinder their understanding of others and influence their actions" (65).

An interesting thing he pointed out was how he gave specific traits from Jungian theory to his main characters in his comic book series Zot. I immediately thought of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator test (which I've done for fun and for a couple classes), which was created from Jungian theory. I had never really thought about this test in relation to creating characters though I can see now how this would be a really interesting way to approach characterization in writing. The reason I've been asked to take this test in class was to give myself a better understanding of my preferred method of approaching things and as a way to understand those who differ on approaches... and basically how to recognize the things I would need in a work situation so that I can maintain my sanity. It was also information that could potentially help me to identify and describe strengths and weaknesses.

This reasoning could relate very well to the creation of characters. By knowing or assigning a type you can better flesh out your characters wants and actions/reactions... while also using that to contrast to other characters/types and to try to understand the effects of character interaction.

Something else that can be used effectively in the planning of characters are archetypes. Archetypes are used frequently in writing but they are useful because of the instant recognition of these characters when readers are presented with them (McCloud's example was of characters like Dumbledore from Harry Potter, Gandalf from Lord of the Rings, and Obi Wan from Star Wars).

Next he discusses the importance of variation in the art for your characters. This is an essential part of the creative process... because no one wants to read about or look at the same character throughout your work (boooring!).

"[W]hether you plan to the last detail or prefer to wing it, your goal should be the same -- to figure out what makes each character unique and to put those qualities front and center" (77).

He talks about some questions artists should be asking themselves as far as whether your characters are too cookie cutter or not. Are your characters all the same height when lined up? Do you keep drawing the same nose and upper lip over and over? Is every woman you draw the same build?

Not that I can really talk since I am unable to draw a straight line... But there are some comic artists I'd love to send these pages to. I have already complained here about the content of Marvel Divas but the art was also an issue.

Cough cough, same body type. Cough!

Moving on. Another thing he mentioned was using stereotypes in comics. He said that they could be used to your advantage (and they can) but he also mentioned contradicting them and punching holes in them (yes, please).

The unifying message for the section regarding art seemed to be to research and come to a greater understanding of the complicated processes involved in human anatomy and movement so that you can make more simplistic decisions regarding them. Most of what comics do effectively as far as character art goes is the result of invisible decisions made by the author and artist. Things like facial expressions, gestures, inner life, and symbols are all crucially important to the readers understanding of the content and all aspects must be considered carefully in order to be utilized as effectively as possible.

"Just remember that in any comics panel, it's the message of your character's gesture that readers will be waiting for, and the first job of figure drawing is to deliver that message loud and clear" (115).

Environment/Setting and Tools

"Want to know the secret of drawing great backgrounds? Don't think of them as 'backgrounds!' These are environments. The places your characters exist within -- not just backdrops to throw behind them as an afterthought" (178).

The environment of your story is yet another important thing to consider. This is what will draw your reader more firmly into your world (and keep them coming back for more). In general the effort of making a detailed setting for your characters is worth the effort. It's challenging to do but important and McCloud offered up the tip of making sure you do your research (which a lot of people leave out of their process). Not only is it easy to use the web for reference but he also suggests going to locations near you to take pictures, sketch, and become fully immersed in. It's like Alan Moore said about character development -- go see the real thing sometime.

There are cases where your art won't need to be as detailed like in emotionally driven stories, but ones that create new worlds should absolutely be detailed if you want your readers to understand what's going on. He mentioned scifi as one of those genres where art should be detailed and from a readers perspective I couldn't agree more. I love scifi related movies and TV shows but I rarely read scifi novels because I often have trouble visualizing some of the things the author talks about.

As far as tools go, McCloud talks about some of the various art tools and the benefit/downside of each. He also discusses the differences between online and print work and how the art differs there. Price and preference dictate how most tools are used and how work is produced.

"Serious comics have been drawn using simple tools before (Maus was drawn with a fountain pen, much of it on ordinary typing paper)" (189).

The Infinite Potential for Comics and the Manga Revolution

"For decades, each generation of comics creators has dug a little deeper into the emotional lives of their characters. Digging deeper still could be one of the ways that future generations of creators will define themselves" (121).

McCloud talks extensively about the potential comics have for evolution. Most interesting to me was a discussion on how manga has influenced a new generation of American artists. Something I never realized that he points out is the audience participation involved in manga. Scenes are set up at different angles, movement is shown around still characters (to suck the reader into the action), and -- on the other hand -- expressions and emotions are focused on rather than action (to suck readers into the emotion of the experience). Moves like these contribute to bringing the reader more firmly into the action and a lot of these things weren't being done in American comics years ago.

I never really thought of this aspect of manga before but it makes me wonder now if the audience participation aspect wasn't what drew me to it. When I was young (11-12ish) I read American comics for a year or two before discovering manga and becoming obsessed with it and reading nothing but Japanese comics up until college. Of course, I still can't say for sure why I turned away from American comics for so long, but it's interesting to now be able to recognize what one of the probable draws of manga was for me.

The end of this book made me think of the possibilities for comics evolution. McCloud points out that the next generation of comics artists and authors are likely to be people who grew up enjoying manga. It is intensely interesting to think of how concepts from manga could be incorporated into American comics.

Final thoughts from Making Comics?

"In short: discovering your own 'style' is a deeply personal process which can take years -- and it can't be taught in a book" (217).

Reinventing Comics

In the sections of the book I've read so far McCloud has been discussing the hopes for comic books in the 90s (and the dashing of those hopes) and the potential for comics in the future. He talks about those of us who are drawn to comics and what they can do, and those who still debate what category comics fall under. There is also history on what has happened to comic writers and artists in the past and the lopsided agreements some were forced to sign that gave them meager rights to their own creations.

Comic books have a pretty turbulent past and have had to reinvent themselves to survive. This reinvention is essential though and not only for survival. As Moore said about not letting your creativity stagnate in the familiar... Don't let comics stagnate in the same formula and content that it has always contained.

So What?

The future of comics was on my mind as I finished my reading this week. McCloud mentioned the influence of manga on future comics and it made me think of the popularity of manga in the US. It has gone from having a couple shelves at major book stores to having full aisles of its own. In fact, there is more space for manga than there is for American comics. There is also representation of manga in comic stores.

I think American comics are steadily evolving and becoming more respected (though they still have some way to go). As this continues in the years to come I wonder about what direction comic book publishing companies will take and how I could potentially be part of the changes that will come. My generation and the ones that follow could make comics bigger than they've ever been in this country and this trend already seems to be in motion when graphic novels like Maus are being placed in the biography section of major bookstores.

Saturday, February 13, 2010 | Labels: making comics, reinventing comics, scott mccloud | 0 Comments

...like everything else in this retarded bastard medium...

"The approach to characterization in comic books has evolved, like everything else in this retarded bastard medium, at a painfully slow pace over the last 30 or 40 years" (Moore 23).

This week I read Alan Moore's Writing for Comics and the first part of Scott McCloud's Making Comics.

Making Comics

The first half of Making Comics is mostly full of tips and some standard rules for comic making. The introduction ends with "In short, there are no rules" at the end of the page, which is followed by a small panel (surrounded by white space) on the next page that says "And here they are."

He starts out the book by talking about the importance of clarity, persuasion, and intensity -- and about the constant choices that need to be made regarding imagery, pacing, dialogue, composition, gesture, etc. He breaks these down into five different types of choices and also refers back to the scene change choices he discussed in Understanding Comics.

The five choices are of movement, frame, image, word, and flow. McCloud talks extensively on the importance of how you establish your opening scenes to create a sense of place for your reader -- and to keep in mind how they will perceive things. There are so many things to consider when making a comic and a lot of details to keep in mind. You also have to keep in mind what you can actually do and then execute it in a quick, clear, and compelling way.

The most important question (or the first, as McCloud says) is will readers get the message? He points out that a style that may be more crude or simple can still win more fans than the best drawn comics out there if it is communicating effectively.

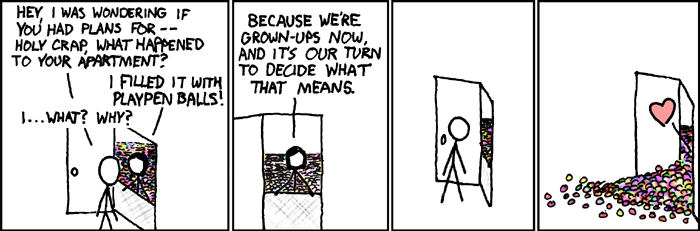

When he mentioned this I thought about the webcomics I follow regularly and about the art that each contains. Xkcd is an excellent example of what McCloud was talking about.

The art for xkcd is very simple. The artist doesn't stray from using stick figures in every comic but there is no meaning lost because of this. The comic has a huge fan following (as well it should!) and you can even buy xkcd merchandise if you want. The point is... this is a very simple style of art... but because of the ideas and humor it successfully gets across to its readers it is effective without needing to be fancy.

McCloud also points out the importance of pictures and words working seamlessly so that readers don't notice a switch. He also mentions this in relation to other aspects with the clear message being to not take your reader out of the story (needlessly).

The bottom line of this part of Making Comics was to remember that your readers are all human beings and therefore at least somewhat predictable. There are a lot of choices to be considered and made when creating comics and a lot of balancing to be done. I think McCloud seemed to most emphasize the importance of making things work for the reader and I agree. Moore also talks about this (and adds in some lovely snark).

Writing for Comics

"You can produce a comic about bright and interesting new characters, have a computer draw it, publish it in a lavish Baxter package and color it with the most sophisticated laser scan techniques available, and the chances are that it will still be tepid, barely readable shit" (2-3).

Moore says a lot about the pitfalls of comics like the fact that they really aren't comparable to any other medium (despite the attempts to do so). He talks about how a lot of lingo is similar to movie making as far as how it will look, but in the end movies are doing something that comics can't and comics are doing something that movies can't. The pacing of comics and other mediums are different and that should absolutely be taken into account.

Some other pitfalls that he gets into involve the style and voice of the author -- he advocates going out and meeting some real people and seeing how they act to develop your story, rather than looking at how other comics writers and artists portrayed their characters. He also talks a lot about self reflection and looking deeply into yourself to pull out every piece to examine. As McCloud also touched on... we're all human and it's very likely that a human is going to be reading your work. Moore also connects this to the readers experience and the importance of the reader (like McCloud).

He got on the topic of self reflection and humanity because, as he points out, there are some comic book publishing companies who think that keeping a tight leash on comics is important so as not to offend any person (ever). This essay was written in the 80s and I feel like this is less the case now than it was then because companies realized readers wanted something more real that they could connect to (something with real emotion, if not necessarily a story about something realistic). The comics of old definitely fit this bill -- and comics had to contend with the comics code authority breathing down its neck for a long time too.

This is obviously not the case as far as women in comics go. Publishing companies like DC and Marvel (especially Marvel) offend women pretty frequently. Most recently Marvel published a series called Marvel Divas where several Marvel girls starred in the series and were essentially copies of the gals from Sex and the City. Now, I like SatC... but I don't want superheroines starring in a comic where they essentially play out SatC and neglect the fact that this is a comic book with superheroes. That's not what I'm buying comics for. On the other side of the fence is Gotham City Sirens by DC, a series where Catwoman, Poison Ivy, and Harley Quinn have teamed up. I have read every issue so far and while I will admit that there hasn't been much of a plot (except for in the more recent issue) yet... at least my comic book girls are still acting like comic book girls and having campy fun while kicking ass. And they've also successfully inserted humorous domestic stuff that doesn't make me feel like I'm no longer reading a comic book (not that this is a rarity in comics, what I'm getting at is they have balanced what Divas failed to).

I won't go into any more examples of how DC and Marvel have offended women recently. I am especially not going to talk about any "that's not how anatomy works" moments.

Anyway, I will say that comics have progressed even more from the things Moore was talking about. My favorite example being Catwoman's progression in comics (because I love her and she and Batman got me into comics in the first place). When looking at the picture as a whole Catwoman has come a long way -- she started out as a sort-of villain for Batman... She was a cat burglar and fell in love with Batman... which meant that eventually her character boiled down to "Batman's sometimes love interest who secretly just wants to marry him and settle down but is going to sort of be a villain for fun for now." Puke! Keep in mind that this was in the 40s though.

Catwoman today is an anti-hero.

I could go on and on about what a strong character she is (and she is!) but the most important thing I want to note is that characterization has come a long way -- even since Moore wrote this.

He talks about the fact that the thought used to be "If a character can't be summed up in 15 words then it may not sell to small children, who we assume are of limited intelligence and possess brief attention spans" (24). I definitely agree with this... and the characterization of Catwoman in the 40s that I summed up fits this. I think in a lot of cases certain people still think this is how it is with comic books. But we are definitely seeing a shift.

Moore also talks about the constant change in comics, just as McCloud did in Understanding Comics. The last essay of the book states this again (it was written in 2003 by Moore) after Moore warns us that he was young and stupid when he wrote the original essays. And he challenges the reader again -- examine yourself and your experiences. And more importantly, don't let your creativity stagnate in the familiar. Constantly push yourself off that next cliff and do things you think aren't possible. If people come to expect you to create comics that are deep and morose then make your next project one that is funny and frivolous.

All of this is good advice -- challenging yourself is important. Though I would say to take this into account once you're already established. Or to do it if creating comics isn't your day job.

So What?

Again I was left thinking of the limitless possibilities comics present and the invisible work that goes into them. Careful planning and good instincts were again touched upon and I wonder how my own instincts would work if I tried to apply them to making comics rather than reading them.

I'm still curious as to the role others play in the creation of comics (besides the author and the artist).

I also checked out Scott McCloud's twitter and was a bit geeked to find out he not only follows a lot of cool comic book artists and authors (of course he does) but he also has a couple of webcomic artists listed as well (like Jeph Jacques of Questionable Content).

Saturday, February 06, 2010 | Labels: alan moore, making comics, scott mccloud, week 4, writing for comics | 0 Comments

Comics! I love comics.

The first chicken on my chopping block is Eisner/Miller. Will Eisner was, at the time, comics’ oldest living Renaissance man. Frank Miller has become an elder statesman in his own right, though he comes off as a young maverick by comparison. I’m familiar with much of their work. I’ve read from Eisner:

- A collected volume of The Spirit

- A Contract With God

- The Dreamer

- The Big City

- The Building

- City People Notebook

- Invisible People

- A Family Matter

- Minor Miracles

And from Miller:

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

- Batman: Year One

- Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again

- All seven volumes of Sin City

- The first couple issues of All Star Batman and Robin

- A smattering of 300

The book is an extensive Playboy-esque interview with the two masters. It’s a conversational affair, conducted in 2002. Eisner sadly didn’t live to see the book’s publication in 2005, though I find that it stands as a remarkable document of his perspective on life and comics in his final years. For Miller’s part, it’s fun to see him in a dual role as both gadfly and gadfly victim. He and Eisner frequently disagree with, provoke, and otherwise agitate one another, though it’s always in the spirit of friendliness. There is a tremendous undercurrent of mutual respect between the two of them.

I’ve read the book a few times, though this is the first time I’ve read it with a defined goal in mind. I’m specifically reading with an eye for useful technical information. Given the wide-ranging nature of the book, there are large sections that won’t yield much of this information, and others that will yield an abundance of it. As far as what I agree or disagree with, I certainly can’t begrudge either of them their own personal working quirks. I’m sure I’ll find out in due time which techniques work for me and which do not. My own work in comics so far only amounts to a couple of silly projects for my own amusement.

I suppose my major hanging question at this point is, “What questions should I be asking that I’m not?” Every piece of potentially useful information is a revelation, not only of answers to my questions, but of questions that I didn’t think to ask in the first place.

Halfway through my current read-through, I’ve adopted a certain strategy in pulling out information that I believe will be useful. Rather than organize notes page by page and chapter by chapter, I’ve attempted to structure them by subject. Each note is annotated with a certain technical theme—“color,” “lettering,” “format,” and so forth—to maximize its usefulness when it comes time to apply what I’ve learned. Those themes will form the sub-headers under which I’ll group the notes in my entries.

THE TRADITIONAL FORMAT

“The traditional format,” as Eisner and Miller refer to it, is a 32 page pamphlet, constructed essentially of sheets of newsprint (size 8.5x22) folded in half and stapled together. This has been the predominant way of the major publishing houses for decades, though they’ve started to adopt higher quality glossy paper in recent years. The current typical price for a monthly issue is $3, up from 10 cents in the 1930s.

Miller argues that the vertical orientation of the traditional format takes its cue from prose books, whereas a horizontal orientation would bring it closer to an art book or a Sunday comic strip. It is also his contention that stories involving broad, visually important landscapes are better served by horizontal orientation, as in his book 300. The human eye has developed to deal with landscape in a horizontal way.

Eisner and Miller discuss different sizes as well. Eisner’s preference was for smaller page sizes, which they believe to have a more intimate, personal relationship with the reader. Larger page sizes create a more communal atmosphere, like an art book. There is also the purely functional concern that smaller-sized books are easier to carry. Miller complains that the traditional format is stuck somewhere in between, that it is neither here nor there. (pp. 11-14)

***

COLOR VS. B&W

Once again, Eisner brings up intimacy, this time in the context of color—or lack thereof. One of the interesting commonalities between Eisner and Miller is that both have worked prominently in black and white. Most of Eisner’s work since his return to comics in the 1970s was done in black and white (or, on occasion, brown and white). Miller’s Sin City series deals primarily with black and white, though he does some experimentation in selective coloring in later volumes. They discuss what they believe to be a quality of greater intimacy that black and white possesses. Artists using black and white are forced to be especially mindful of shapes and lines, which gain greater purposefulness in the absence of color.

They agree that comics done in colorful have an almost musical quality, comparing bright colors with the grandness of opera. Eisner argues that many comics don’t utilize color purposefully, that it is more of a marketing tool designed to grab the reader’s eye in the store. He argues that some stories would be better served by black and white, using the metaphor of Edith Piaf being accompanied by full-scale operatic music.

Miller observes that, in the advent of limitless computer colors, modern mainstream comics have acquired an unattractive aesthetic, that they’re too “airbrushed,” “tight,” and “brown.” He finds that consciously limiting the use of color can lend colors a greater weight and importance. Eisner also posits that black and white comics are read like books, whereas color comics are looked at—or “absorbed porously,” in his words. (pp. 16-21)

***

Aside from intimacy, the especially bold use of black and white can really grab the reader “by the lapels,” as Frank Miller puts it. (p. 43)

***

BALLOONS AND LETTERING

In discussing Eisner’s lettering in A Contract With God, Eisner and Miller decide that oversize lettering imparts an almost childlike quality to the reader, which draws them in and engages their curiosity. (p. 22)

***

Eisner harkens back to the 1930s, when many newspapers were actively deciding to improve the quality of their comic strips. Their basic strategy was to bring in good illustrators—for example, Alex Raymond (of the Flash Gordon comic strip). The incoming crop of artists was given the goal of improving the comics and making them appeal to a broader, more sophisticated audience.

One of the tricks they tried was experimenting with typeset, as opposed to the standard hand lettering. The comic strip Barnaby featured dialogue balloons that were lettered in typeset. A more modern-day example would be Hal Foster’s series Prince Valiant, which features typeset lettering exclusively, and also does away with balloons entirely. Eisner and Miller are both critical of this decision, arguing that typeset creates a sterility that clashes with the hand-drawn aesthetic of comics.

An artist whom Eisner and Miller single out for his distinctive, expressive lettering style is Al Capp (Li’l Abner). The size and weight of Capp’s lettering wax and wane, depending on the emotional content of the words being spoken. With its enormity and boldness, some of Capp’s dialogue practically “shouts” at the reader. (pp. 29-39)

***

ATMOSPHERE/ENVIRONMENT

Evoking atmosphere is an important aspect of comics storytelling. Rather than merely relating the story to a passive reader, a comic with a strong sense of atmosphere draws in and engages the reader actively. It makes the reader feel things. Eisner and Miller use the example of a character walking in the rain, which they’ve both made prominent use of—Eisner in A Contract With God, and Miller with the first Sin City story. Purely with the visual, they craft the atmosphere and build a sense of tension.

They also discuss techniques by which atmosphere can be dealt with, and cited Milton Caniff’s method of creating snow as an example. If Caniff wanted to draw a house in the middle of a blizzard, he’d simply do the dark shape of the house, against a white background, blot it out with a few snow-shapes, and throw in a couple of white squares for windows. It’s the simplicity of the illusion that makes it work. (pp. 22-27)

***

One of Eisner’s tricks for creating a sense of atmosphere, which Miller used prominently in his early 1980s work on Daredevil, was drawing floating bits of paper to indicate moving air. Another tried-and-true Eisner technique is the use of rain. The reasoning is that everybody knows what wind and rain feel like, so implying a sense of wind and rain in the drawings will draw viscerally upon those associations. Drawing flies above a garbage can will imply to the reader that there is a stinky smell afoot. Drawing visible beams from a car’s headlights can imply dust or fog. There are other feelings an artist can find ways to refer to as well, such as heat or cold. (p. 42)

***

In much of Eisner’s later work, he uses wash (broad brush strokes made with a mix of ink and water) to create “soft” backgrounds. This implies a sense of depth. The technique mimics the way that the human eye and cameras both tend to focus only on objects at a certain distance, with everything else appearing out-of-focus. Miller refers to this as “depth of field,” borrowing the term from photography.

For a long time, and to this day in the mainstream industry, it was considered professionally standard to be able to draw complete backgrounds, in every panel at any angle. Eisner’s approach is to the contrary. Rather than spend so much time and attention on backgrounds, he takes the most important parts of the scene—objects, characters, or whatever—and constructs the scene and the background around them. He uses a few significant details (like a desk with a lamp on it, to use their example) to imply what kind of room it is, what era it’s in, what’s happening, who lives there, and so on. As an influence, he cites the old low budget Works Project Administration theaters that he went to during the impression, which made use of fairly Spartan stage settings.

It is Eisner’s contention that he and Miller work alike in this way. Their artwork is similar to the way that the human brain remembers things, which is impressionistic and tends to emphasize the key details of events and moments.

This approach also subtly works to draw the reader in through active engagement. When presented with an incomplete set of details, the reader will subconsciously work to fill in the blanks. In a more general sense, this is what comics do as a whole, presenting a series of “snapshots” that the readers connect together as ongoing action in their minds. (pp. 59-62)

***

WHAT COMICS CAN DO

In discussing the unique traits of comics, Miller cites a trick he often uses in his work on Batman, which is to create a single overriding image (such as a page-size drawing of the character’s face) and then intersperse several small panels of separate moments within. This creates a sense of instantaneousness, as though there are many individual events happening simultaneously. Miller likens this to the experience of channel-surfing on television.

Eisner discusses his own work in terms of live theater, where the compositions aren’t necessarily viewed from subjective angles (whereas they are in most comics, as well as in film and television, for that matter). He tends to go from a more objective point of view, which is nevertheless subject to the sort of artistic manipulation that wouldn’t be possible in actual live theater. This is in contrast with the style he worked within during his days of The Spirit, using subjective viewpoints which Eisner referred to as “cinematic.” As cinema was the budding popular art form of the times, he felt he would be conversing with the audience in the language that they were familiar with. (pp. 87-93)

***

WHAT COMICS CAN’T DO

While the masters of comics will loudly and proudly advocate for what comics can do that other media cannot, Eisner and Miller also discuss the practical concerns of what comics can’t do. It is therefore important that a comics storyteller be able to imply certain things that they can’t deal in directly. Among those things are sound, motion, and the passage of time. (p. 27)

***

One way that storytellers compensate for the lack of sound in comics is through the dialogue balloon, which Eisner refers to as a desperation device. It is a utilitarian way of indicating which characters are talking and what they are saying, which is still in use mainly because artists who have attempted to improve upon them or do away with them (including Eisner himself) have found their efforts frustrated. In the end, the best way to handle balloons is to ensure that they’re as unintrusive and as connected to the action as possible.

There are things artists sometimes do that violate the connection between the balloons and the action (and, by extension, between the balloons and the reader), such as so-called “umbilical balloons,” which are multiple balloons joined together in one passage of speech. There is also the use of typeset in balloons. Eisner criticizes Harvey Kurtzman (of EC Comics in the 1950s) for doing both. (pp. 30-35)

***

In dealing with the absence of motion, artists must often exaggerate their drawings to convey the illusion of motion. For example, Frank Miller discusses his frequent drawings of moving cars in Sin City, pointing out that a realistic drawing of a car will look like it’s parked, whether it’s supposed to be moving or not. His Sin City cars are often drawn ten feet off the ground as they’re careening over a hill, an image which tells the reader that it must be in motion. Most readers have ridden in a quickly moving vehicle, which will sometimes give the gut feeling that its wheels are leaving the ground. It is this impression that Miller wishes to give his readers. Nobody gets that feeling while sitting in a parked car, at least, not normally. (p. 39)

***

When implying time, the artist must be mindful of pacing. Comics has no intrinsic control over pacing—the reader has full control—but there are things the artist can do to induce the reader to take the material in at a certain rate. As Miller says, the line drawings in many of today’s mainstream comics has a very dense aesthetic, which many people mistakenly think of as very detailed. (As Miller cautions, detail and density of line are not the same thing.) Higher line density tends to slow the reader down, while very simple, wide open, airy drawings tend to encourage the reader to speed up. (p. 65)

***

Another way that Eisner and Miller discuss to create an illusion of slowed pacing is to charm the reader’s eye—to create an image so compelling that the reader will be induced to linger for a moment, in contrast to images that are designed to be viewed and released quickly. Similarly, the image could be used to induce confusion in the reader, to momentarily bewilder the eye in such a way that it takes a moment to make sense of it. This is a much riskier option, in that a momentarily confusing image could easily just be a confusing image, period. And, other things being equal, a scene with a lot of dialogue will move more slowly than a scene with very little dialogue, or none at all. (p. 93)

***

THE WORKING PROCESS

When embarking on a new story, Eisner likes to start with the characters. He spends time “casting” them, sketching their faces, figuring out their names, who they are, how they relate to each other, and so on. For works that span a very long period of time, such as The Name of the Game, he puts together a timeline to figure out where they are and what they’re doing at any given time period. When he has that figured out, he’ll put together a basic biography of each character to figure out their development over time. On a personal note, this may work for Eisner’s broad approach at characterization, though I’d be more personally inclined to start with the character biographies and then figure out how they play out over time, because I fear turning my work into an obviously plot-driven artifice. But that’s just me, and to each his/her/its own.

From there, Eisner develops a list of scenes, or “incidents.” He doesn’t necessarily do this chronologically; in fact, he tries to keep the ending in mind from fairly early on. Miller has a similar method with developing his plot. He puts each individual incident on a Post-It note, and then puts all the Post-It notes on his wall. He’ll then spend some time rearranging them until he feels they’re in the right order for his story. If he gets lost, confused, or unsure at any time, all he has to do is look at the wall for the complete picture.

In relations with the publisher, Eisner shows his early artwork, whereas Miller tends to relate where he’s at and what’s happening in his story verbally. This perhaps evinces less trust for authority on Miller’s part, which is probably unsurprising to anybody familiar with his work.

Neither Miller nor Eisner think of pencil drawings as finished artwork. Pencil drawings are either sketches or a mere early stage of finished artwork, functioning more as a document of the art rather than the art in itself. It’s worth noting that other artists have experimented with using pencil drawings as finished artwork, though it’s not a widespread approach. The most common way is to start with rough pencils, then tight inking of the lines (with perhaps a stage of tight pencils in between), then inking of the broad, flat black areas.

Eisner figures out where his balloons go at an early stage of the drawing, to ensure that they mesh well with the whole composition. He spends a lot of time on character postures, gestures, and other such small details. He tends to work on one page at a time, from pencils at the beginning to the fully inked final art.

He also prefers that each page end on the completion of an action, rather than dividing actions between pages. He feels that his way is for the best, in terms of rhythm.

Miller’s process is idiosyncratic. He works in blue pencil, which is designed so that it doesn’t show when the finished artwork is photographed. When doing the inks, he does the broad, flat black areas before the fine lines, which is the opposite of what most professional inkers do. He tends to do each stage across all pages, meaning he’ll do the pencil drawings of every page, and then revisit every page for each stage of inking. He refers to the excitement of the momentum this creates during the last stage, during which he’s producing finished pages at a very fast rate. (pp. 71-87)

***

NOTABLE QUOTABLES

“You got to us. We started regarding ourselves as novelists. It’s as if you said, ‘These’ll be permanent.’”

- Frank Miller on Eisner’s groundbreaking A Contract With God (p. 44)

“Technically, I currently work from live theater because I no longer worry about getting bird’s-eye views and special camera angles. When people talked about the cinematic quality of The Spirit, that was because I realized… that movies were creating a visual language and I had to use the same language, because when you are writing to an audience that is speaking Swahili, you’d better write in Swahili.”

- Will Eisner on the difference between the “cinematic” quality of The Spirit and the “live theater” quality of his post-comeback work

Sunday, January 31, 2010 | | 0 Comments

"The mixing of words and pictures is more alchemy than science." (161)

Breakdown, summary, and analysis of Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud

1. setting the record straight

com-ics (kom'iks)n. plural in form, used with a singular verb. 1. Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in a deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.

In this chapter McCloud attempts to establish a more encompassing definition of comics (see above) while giving some back story into what could be considered the oldest comics (Egyptian, pre-Columbian, etc.). He also points out that comics will likely always struggle to find an agreed upon definition thanks to the infinite possibilities they present.

2. the vocabulary of comics

I found this chapter in particular to be enlightening. He points out how we project ourselves and our self image and identity onto things like symbols and objects (while driving our car it becomes an extension of ourselves... if another car collides with ours they are hitting us, not the car). If you see a circle with two dots and a line inside you can't help but see a face when constructed a certain way. It's also easier to project yourself onto an image that is less defined (as in many comics and cartoons). "We assign identities and emotions where none exist."

He also discusses how realistic backgrounds only add to this (being able to project yourself onto the character) and mentions that in the past it was more typical for Europe or Japan to do this in comics. He doesn't mention this but I found this part funny because having read manga for many years I know that in a lot of cases they actually use pictures of real things in their backgrounds. I had never really thought of this before in relations to comics -- obviously escapism is a big part of the reading experience and people tend to project onto their favorite characters but I had never really thought of how art can help this along (at least not in the way he talks about).

3. blood in the gutter

"The comics creator asks us to join in a silent dance of the seen and unseen. The visible and the invisible. This dance is unique to comics. No other art form gives so much to its audience while asking so much from them as well. This is why I think it's a mistake to see comics as a mere hybrid of the graphic arts and prose fiction. What happens between these panels is a magic only comics can create." (92)

This chapter discusses how the space in between the panels is doing some interesting things. "Closure" happens in life and in stories -- where we fill in the blanks of what is real around us even though we haven't or couldn't perceive this with our physical senses. His example of kids thinking things simply don't exist if they're not there to see/do it was good. It's the age old question of, "If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around -- does it make a sound?"

But back to the spaces between panels -- the "gutter." Between the spaces of the gutter things are happening that every reader is going to interpret differently -- which is amazing. His example was a panel of a man holding an axe above his head and aiming for a man who looks to be trying to get away and who yells "no!" The next panel in the sequence is a cityscape at night with a scream written in letters across. As he says... it's in the gutter where a man is (or isn't) killed. The viewer controls the speed and intensity of the axe as the man strikes it against the other. It is up to the viewer to decide how the time in between played out.

Also in this chapter are six types of transitions that happen in the gutter (moment-to-moment, action-to-action, subject-to-subject, scene-to-scene, aspect-to-aspect, non-sequitur) and a break down of how they seem to be utilized in American, European, and Japanese comics. The most interesting aspect of this is the information that Japanese comics more frequently utilize aspect-to-aspect transitions (i.e., transitions between different parts of a scene to give the viewer a full picture). He does mention and I would argue that today this is done more often in American comics than it was in the past (and it's still typical of manga).

Something important he mentions that hits on where future growth in comics could be is with viewer interaction... or a sort of "choose your own adventure" scenario. At first I dismissed this idea because choose your own adventure stuff might limit a writer or writers might not like it in cases where they are trying to take a certain path. Then I thought on it more and I think it could potentially be interesting and open up things a bit for a writer. And to be honest I would argue that this has been done, especially by the bigger comic publishing companies. It's not done in the same comic issue or graphic novel or anything... but these companies are constantly rebooting and reinventing series, events, and characters. With characters like Batman (who has been around for 70+ years) this is kind of inevitable.

4. time frames and 5. living in line

These chapters describe how every single part of the visuals for the comic can be manipulated to give a message to the reader about what is happening. This can be done with panel sizes (e.g., putting a longer panel between two shorter ones to indicate a long pause), text boxes, the way words are written, the way a line looks... And it talks about how visible symbols (like lines over an overturned garbage can that indicate the fact that it stinks) can easily (and have) become invisible. Also important is discussion on the balance between words and pictures in a comic and how those fluctuate.

6. show and tell

In this chapter he talks about the division of art and prose and points out that as children we read books with more pictures (because it's easier) and then gradually we upgrade to less pictures until finally we're reading texts with no graphics (or we're not reading books at all -- shock and horror!). He also points out that language is originally created through familiar/common symbols (which then evolves into something like our alphabet where it represents sound only). I know this very well after several years of Japanese -- when learning to write the language most of our materials would first start out with a drawing of some real thing then slowly break that down until it became the character.

He also points out the sad but true fact that though comics have a much longer history than most people realize... it's still seen as something of a kid next to novels, art, drama, and other such things. This was written over ten years ago now and though things have been making a slow change since then there certainly hasn't been a huge leap in changing the general populations mind on this idea.

7. the six steps

This chapter starts out by saying that art is anything that isn't related to the human need to reproduce and survive. I am very fond of his caveman references such as... caveman sneakily grabbing onto a high tree branch just before racing off a cliff while being pursued by a wild beast leads to the beast falling to its death (survival) after which the caveman proceeds to stick his tongue out at and make a "nah-nah" type noise (art). He talks about the six steps that lead to the creation of things like comics and the journey from surface layer to final vision. The section was very interesting in thinking of how people follow on a path to becoming a comics artist or writer and how some people end up abandoning their goals while others find ways of reinventing what we think of as typical.

8. a word about color and 9. putting it all together

Most reasons for the relationship of comics and color can be summed up by "commerce" and "technology." The color chapter pointed out a lot of interesting things about colorful superhero costumes (and the relationship between the character, the reader, and those colors). This was the only one that could be considered a little outdated. The information is all relevant but this would definitely be a much larger chapter today because of the technological advances we've seen in the past ten years. He also doesn't mention the fact that Japanese manga is typically always in black and white (I don't really know why -- maybe because they tend to produce chapters more quickly and the author doesn't have time to color each page).

So, unfortunately comics still have a ways to go before they're thought of in terms of the definition McCloud has provided (yep, already knew this). I've definitely been made aware of a lot more of the subtle moves that comics artists and writers are making thanks to my reading this though. I really enjoyed his inclusion of examples of European and Japanese comics. I can't help but contrast Japanese manga and American comics when learning about them. I think an awareness of the differences can be important considering how popular manga is becoming in the US (and has become). I think both styles have the potential to influence one another (and have in some cases already).

Next!

Next in my research... I am definitely even more interested in perusing comic scripts (which I will be doing eventually) and seeing how much of the comic is planned out in a certain way and how much is the end result of the artists (or whoevers) instinct. The only questions I have in mind at the moment are about the roles of the people involved in comics. I can guess what most of them are like and that decisions and input are on a case-by-case basis... but I definitely want some actual facts rather than just my own speculation. I am excited to learn more about the invisible processes behind comics.

Friday, January 29, 2010 | Labels: scott mccloud, understanding comics, week 3 | 0 Comments